'Big Hill' has always been a very challenging stretch of railroad

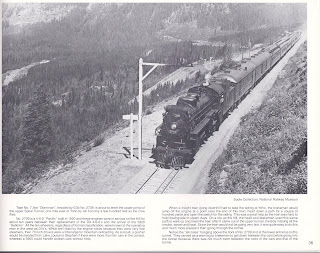

This photo, published in Floyd Yeats' Canadian Pacific's Big Hill (1985), is from the Soole collection at the National Railway Museum in York, England. It shows CPR's The Dominion westbound, about to enter the Upper Spiral Tunnel. Portions of the lower grade are shown in the background.

Three Canadian Pacific railroaders died at 1 a.m. Monday, when their 112-car grain train derailed on what railroaders know as “The Big Hill,” between the summit of Kicking Horse Pass on the B.C.-Alberta boundary, and the town of Field, 10 miles to the west.

News reports and photos of the scene show unbelievable destruction. The lead locomotive apparently went off a bridge into the Kicking Horse River, and at least a Union Pacific trailing locomotive and 99 cars piled up behind it. Only 13 cars and the rear end locomotive stayed on the tracks.

A Transportation Safety Board preliminary report Tuesday indicated that the train had been stopped for a crew change on the upper part of the hill, at Partridge siding. It had been there for two hours, with air brakes applied.

The new crew took over but the train started to move before they were ready. The TSB will now look in detail as to why the brakes apparently failed at that time.

Cold weather may have been a factor.

There are reports that the crew radioed the rail traffic controller shortly before the derailment, saying the train speed was excessive and the train was out of control.

The derailment took place at the bridge near Yoho, between the Upper and Lower Spiral Tunnels. While CP did not allow media to access the site, some very good footage was taken from the nearby highway. The derailment site is quite close to the highway lookout which allows a good view of the Lower Spiral Tunnel, and explains the history of the railway in the area. The highway is built on the original grade.

A Transportation Safety Board preliminary report Tuesday indicated that the train had been stopped for a crew change on the upper part of the hill, at Partridge siding. It had been there for two hours, with air brakes applied.

The new crew took over but the train started to move before they were ready. The TSB will now look in detail as to why the brakes apparently failed at that time.

Cold weather may have been a factor.

There are reports that the crew radioed the rail traffic controller shortly before the derailment, saying the train speed was excessive and the train was out of control.

The derailment took place at the bridge near Yoho, between the Upper and Lower Spiral Tunnels. While CP did not allow media to access the site, some very good footage was taken from the nearby highway. The derailment site is quite close to the highway lookout which allows a good view of the Lower Spiral Tunnel, and explains the history of the railway in the area. The highway is built on the original grade.

Here’s the latest report from the Calgary Herald. Calgary is the head office of Canadian Pacific and the three railroaders all lived in the Calgary area. Engineer Andrew Dockrell had 20 years experience. Also killed were conductor Dylan Paradis and conductor trainee Daniel Waldenberger-Bulmer, who was likely recently hired by CP.

The news of the passing of their loved ones has been very hard on the families. Here are some details. A GoFundMe campaign has been set up by other CP employees to help families deal with the additional expenses they will face. As of Thursday afternoon, it had raised $79,115 towards its $100,000 goal.

The news of the passing of their loved ones has been very hard on the families. Here are some details. A GoFundMe campaign has been set up by other CP employees to help families deal with the additional expenses they will face. As of Thursday afternoon, it had raised $79,115 towards its $100,000 goal.

I don’t want to speculate. This post is meant to, first of all, pay respect to three individuals who lost their lives doing a very dangerous job. Handling a heavy train (it would have weighed more than 10,000 tonnes) down a steep grade is a very tricky task, and requires equipment that is in first-class condition, superb track and many skills in train handling.

The other thing I wanted to do in this post is give a bit of history of “The Big Hill,” so that casual readers know a lot more about just where this took place.

My main source is an excellent book called Canadian Pacific’s Big Hill by the late Floyd Yeats. Published in 1985, it contains many fascinating details about the hill - Canadian Pacific’s most challenging grade - and about the railroaders who worked on it in its first hundred years, 1885-1985. Floyd and his father George both worked as enginemen on the hill and knew every inch of it. Floyd was born in Field 100 years ago.

This map of the CP rail line on the Big Hill was drawn by Geoffrey Lester, and is published in Floyd Yeats' Canadian Pacific's Big Hill. The book came out in 1985, and was published by British Railway Modellers of North America, Calgary Group.

When the rail line was first built between Stephen (at the summit) and Field, it had a 4.5 per cent grade - twice that of today. Trains were very short, but equipment was very primitive. There were three “safety” tracks, similar to the runaway lanes seen on steep mountain highways for out-of-control trucks to use. These safety tracks always had the switch set for the spur, not the main line.

Here is how Floyd Yeats describes them, and explains the procedure used to handle trains down the hill.

“These (safety) tracks were located above the bridge over the Kicking Horse River (west of Wapta Lake); a short distance east of the site now known as Yoho (on the stretch of track between the two Spiral Tunnels); and above the present Cathedral siding (just east of Field).”

This is how trains were handled at that time.

”Operating procedures for westbound trains were rigid and strictly adhered to, as illustrated by the following extracts from the 1909 employees timetable,” Yeats wrote.

“One long whistle must be sounded at the whistle board located about 1,000 feet east of each safety switch. Provided the train is fully under control and not exceeding the prescribed speed, four short blasts must be sounded at the sign board showing switch number, as a signal for the switch to be thrown for the main line. The normal position of a safety switch is for the spur, and an engineer must not whistle for a switch unless his train is within the required limit (of eight miles per hour for passenger trains, and six for freight trains) and he is satisfied he can maintain it so.

“If a train is seen to be running faster, for any cause, than its prescribed speed, the electric gong must be sounded by pressing the button in the watch shack, which will be a signal to all switchmen and the operator at Field that a train is ruinning too fast.”

By 1909, the construction of the Spiral Tunnels, which reduced the grade to 2.2 per cent, was well underway. The new line was opened to traffic that year, adding four miles of distance and two world-renowned tunnels to make the grade more manageable. The safety switches were pulled out when the new line opened.

There have been accidents on the hill over the past 134 years, including a derailment at the Upper Spiral Tunnel on Jan. 3. Thankfully, most have not involved the loss of life.

Let's not forget these three railroaders, who lost their lives while doing their jobs in a very challenging workplace environment.

Let's not forget these three railroaders, who lost their lives while doing their jobs in a very challenging workplace environment.

Comments

Post a Comment